What is depression?

A little light from Jung…

Depression is probably the most likely symptom to make a person seek out the help of a psychiatrist or psychotherapist. As a symptom it has a wide field of gradations ranging from a general feeling of low morale to a dark tormented condition of hopelessness which in severe cases can result in suicide. In the former state we might do well not to pathologise since periodic fluctuations of mood are normal and a natural counterpart to periods of happiness and as James Hollis observes “Could we even imagine the possibility of joy if we could not contrast it with its opposite?” (Hollis, 1996) Seen in this light a periodic feeling of low morale interspersed with periods of brighter moods is a natural and true consequence of being alive. Thus a certain amount of depression within a life is normal and healthy.

Psychiatry in the past divided depression into ‘neurotic’ and ‘psychotic’ varieties. The neurotic type was often termed ‘reactive’ meaning that the sufferer in this state was reacting to a significant event that was thought to have been the genesis of the depression. This might include a broken love affair, a bereavement or loss of employment. The psychotic form of depression however was thought to be endogenous, i.e. having its genesis in the personality of the sufferer without being set off by external events. In this form the depression is more likely to be accompanied by symptoms such as weight loss, insomnia or other psychosomatic conditions. In such cases a psychiatrist is likely to prescribe ant-depressant drugs without recourse to an in-depth analysis of the patient’s personality in order to find the root causes. (Storr, 1990)

Social factors may play an important role in cases of depression even when there is so definable traumatic event that may set it off. Women are particularly vulnerable to depression brought on by social factors, which can include being stuck in an unsatisfactory marriage, living under poor conditions, having 3 or more children under the age of 14 at home and generally having no life outside these restrictive factors. Chronic ill-health also can also an make a person more vulnerable to depression.

Depression can be thought of as a ‘disorder’ only when there is a certain predisposition towards it. Thus in a normal case of depression an adverse life event may set if off and yet the person can return to their normal state of equilibrium after a certain period. How long this might take is not quantifiable and would depend on the individual circumstances and the severity of the precipitating event. When the depression becomes a disorder – i.e. it can be thought of as pathological – then the person cannot return to the state of equilibrium and remains in a depressed sate.

Once a thing has fallen into the unconscious it is retained there, regardless of whether the conscious mind suffers or not. (C.G. Jung)

The characteristics of the depression in any one case would depend on whether it could be classified as ‘simple’ or ‘melancholic’. In a simple depression the tone is one of “feelings of weakness, lack of motivation, pessimism and loneliness.” (Steinberg , 1989). In melancholic depression however the symptoms are more severe, characterised by a “profound and overwhelming feeling of self-blame, hopelessness and self-deprecation. Such people suffer from a pervasive melancholia, disorder of thought processes, psychomotor retardation and somatic dysfunctions. Their thoughts are gloomy and morbid.” (ibid.p339-340)

Depression around mid-life is very common and in Jungian terms can be thought of as an inevitable collision between the ego, which may have developed in less than ideal circumstances in the first half of life, and the Self which wishes to be in the foreground in the second half of life. The collision of these two opposing forces creates a depression.

Jung himself did not evolve a theory of depression in itself but, in fact, saw all symptomology as basic to the alienated state of human kind in general where dissociation of the personality is the norm, involving projection of the contents of the unconscious rather than integration of them and thereby enlargement of the personality. Thus for example, a man possessed by his anima, “a creature without relationships” is prey to a “moody and uncontrolled disposition” (Jung, CW16 para. 504). Jung is always looking for the archetypal background of symptomology so the symptom itself is not a main source of focus for him. Thus he considers depressions, moods, nervous disorders as the appearance of certain psychic contents “which express themselves by their power to thwart our will (and) to obsess our consciousness.” (Jung, CW7 para. 400) These psychic contents Jung argues are a manifestation of God and to deny this is an act of repression and the personality as a result becomes impoverished. He argues that this impoverishment comes about because contemporary experience and knowledge , which is characteristically rational and one-sided, regard the experience of symptoms like depression as valueless and meaningless, something to be gotten rid of, when in fact on a higher level of experience they lead the way to wholeness via integration of unconscious contents.

Could we even imagine the possibility of joy if we could not contrast it with its opposite. (James Hollis)

These unconscious contents carry a charge of libido and since this libido is trapped in the unconscious through a characteristic one-sided attitude of the ego then the ego itself is depleted of energy. In speaking of the depressive world of one of his patients Jung remarks

“The patient’s world has become cold, empty and grey; but his unconscious is activated, powerful, and rich. It is characteristic of the nature of the unconscious psyche that it is sufficient unto itself and knows no human considerations. Once a thing has fallen into the unconscious it is retained there, regardless of whether the conscious mind suffers or not. The latter can hunger or freeze, while everything in the unconscious becomes verdant and blossoms.” (ibid. para. 345)

Because the development of the ego in the first half of life has to be one-sided to fit in with certain circumstances, libido builds up in the unconscious as a counter-position to the conscious one. Through time and further repression of contents it has the power to invalidate all conscious contents. Thus in the above case that Jung cites the depression was caused by negative feelings that were “so many autosuggestions” which were accepted without argument by the patient, despite him being a “very clever young man who had been intellectually enlightened” (ibid. para. 344)

The dynamics of depression are thus to be thought of with reference to the concepts of compensation and introversion. The unconscious compensates for the one-sided attitude of consciousness by causing libido to be diverted from the object-world through the process of introversion leaving the ego depleted of libido which causes depression. In order for the depression to be lifted the unconscious contents must be integrated, contents which may be wildy different from the conscious standpoint, and this leads the ego to be replenished by the libido which can flow freely. In the above case the conscious attitude of the patient was so one-sidedly rational that nature rose up and annihilated his whole world of conscious values.

The depression turns out to have been trying to realise something, is directed towards a goal and this goal is transformation.

This introversion of libido and the depressive state Jung sees as a kind of marker as to where the ego needs to go to be replenished. The patient must look back into the depths of the depressive state which has links to the past, to the personal unconscious, insofar as the past is an object of memory and therefore a psychic content. Jung says this can only be done by “consciously regressing along with the depressive tendency and integrating the memories so activated into the conscious mind – which was what the depression was aiming at in the first place.” (Jung, CW5 para. 625)

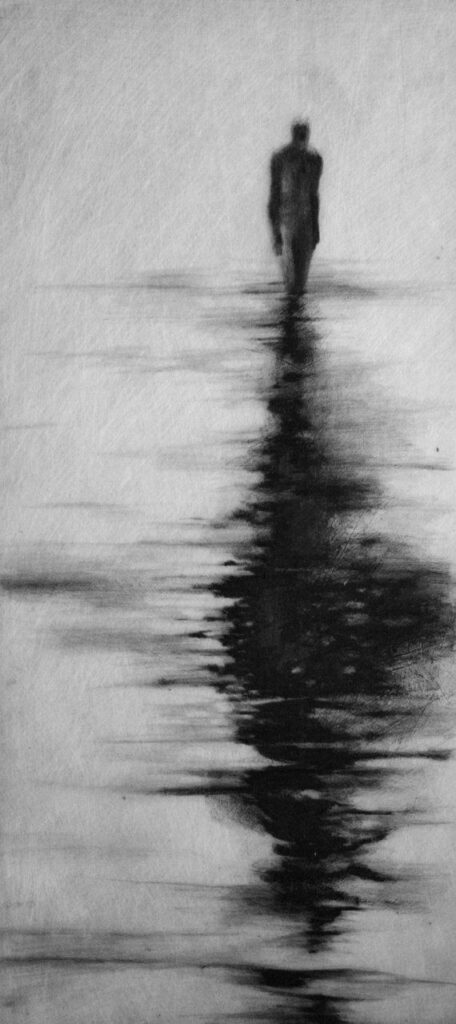

The depression turns out to have been trying to realise something, is directed towards a goal and this goal is transformation. This goal represents a “regression of energy in service to the Self” (Hollis, p.73) This Type of depression is what Esther Harding calls a “creative depression” and the hero’s descent into the underworld is it’s primary myth. The hero entering the underworld can be seen symbolically as the introversion and following back of libido and the encounter with the monster or dragon as some unconscious affect associated to a complex or archetype. and inasmuch as the hero is changed by the encounter, he has died. The introversion process itself is accompanied by depression firstly because the ego becomes depleted as energy is drawn towards the unconscious and secondly because change itself is always symbolised as death and this prospect, the death of long held values and beliefs, is naturally accompanied by depression. The symbolic experience of death can also be confused with actual death and this can lead to obsessive fantasies revolving around disease. The analysand going through such a rebirth experience can become convinced that actual death is around the corner. Steinberg relates such a case where “the symptom became so strong and the affect so real that “even his wife, who was a physician, was convinced.” (Steinberg, op. cit. p.342) However, after thorough analysis of dream material the analysand realised his paranoia was related to psychological change rather than actual physical death.

Jung’s approach to depression is consistent with his ideas on how the personality is structured and as such all symptomology can be seen as the withdrawal or redirection of libido from the ego as the centre of the conscious personality.

Recognising that Jung’s main focus was the transformation process and not the , of symptoms, Steinberg has questioned Jung’s (and others) assumptions about the aetiology of depression. One of these assumptions has to do with precipitating events and he argues that actually set backs in life such as the loss of a job often result in strongly adaptive coping behaviour where the libido is progressive rather than regressive, and that therefore a predisposition is an important factor. One significant factor in this predisposition is the severe loss of love early in life leading to the idea that a personal factor was responsible for the loss. This conclusion is usually supported by moral criticisms from the parents and the depressive is always motivated by the need to regain this love by the proper form of ‘redemptive’ behaviour. In this situation an adult can carry the childhood patterns of relationship into adult encounters and find similar relationship patterns in search of this redemption. This concern with primary sources of love makes depressives very sensitive to the environment and significant others, dispelling the observation or assumption that depressives have a lack of interest in the environment. Steinberg argues that the withdrawal evident in depressive states should not be confused with introversion as depressives usually have an extremely extraverted psychology which they have developed as a defence against the loss of love and that the real challenge for them is to develop their introversion by becoming attuned to their own needs rather than trying to satisfy the needs of others to regain their own sense of being loved. This is often plagued with difficulty as the discovery of individual feelings at odds with the environment are most feared because they lead to the threat of the loss of love.

One last thing to mention is the correlation of depression with impounded aggression; either this aggression turned in causes the depression or that the impounded aggression is the result of depressive dynamics. Steinberg put the situation thus;

“The excessive and irrational guilt and self reproach from which depressed individuals suffer is often induced by parents who threaten to withdraw their love from a child unless he conforms. Such threats often centre on a child’s self-assertiveness, which the parents experience as hostile.” (Steinberg, op. cit. p.348)

I can agree with this to a point but my own experience leads me to believe that such situations are rather more complex. For example the parents don’t experience the child’s assertiveness as hostile since depression indicates that the child has failed to be assertive and therefore it is the child’s fear that he or she will be experienced as hostile that is the issue. The child is responding to family dynamics where there is an unconscious agreement between family members that the child does not have any rights to self-assertion. For example when I was 11 years old my mother told me that she was leaving because she had fallen in love with another man. Evidently I was meant to feel very pleased for her to serve her narcissism, which consciously I did. Many years later I told her about my experience and she denied it ever happened and told me that it must be a ‘false memory’. In reality at the time her animus was calling the shots and she was just as much a passive victim as I was. I believe these things stretch much farther back than the immediate situations at which the depressive person is said to have started to develop in a way that leads to depression. My experience is also that the depression or affect does lead into the unconscious, it is purposive and it uncovers a whole nexus of intertwined relationships which are inter-generational, basically primitive insofar as they lead back to ancient kinship customs (Jung, CW16 para. 441) and that bringing consciousness to these configurations does indeed lead to religious experience, insofar as the contrasexual archetypes acting properly as an inner relationship, leads to experience of the Self .

References

Hollis, J. (1996) Swamplands of the Soul Inner City Books p.47

Jung, CG.( 1966) Symbols of Transformation Collected Works Volume 5 London Routledge & Kegan Paul 2nd Edition

Jung, C.G (1966) Two Essays on Analytical Psychology Collected Works Volume 7 London Routledge & Kegan Paul 2nd Edition

Jung, C.G. (1966) The Practise of Psychotherapy Collected Works Volume 16 London Routledge & Kegan Paul 2nd Edition.

Steinberg, W. (1989) Depression: a Discussion of Jung’s Ideas in JAP Vol. 34 issue 4 p. 339

Storr, A. (1990) The Art of Psychotherapy London Routledge

More articles